Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) | Lesson

ADVERTISEMENT

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is one of the most common chronic gastrointestinal conditions, with significant clinical and economic implications. It is characterised by the reflux of gastric contents into the oesophagus, resulting in troublesome symptoms such as heartburn and regurgitation, and, in some cases, complications including oesophagitis, Barrett’s oesophagus and stricture formation (narrowing of oesophagus).

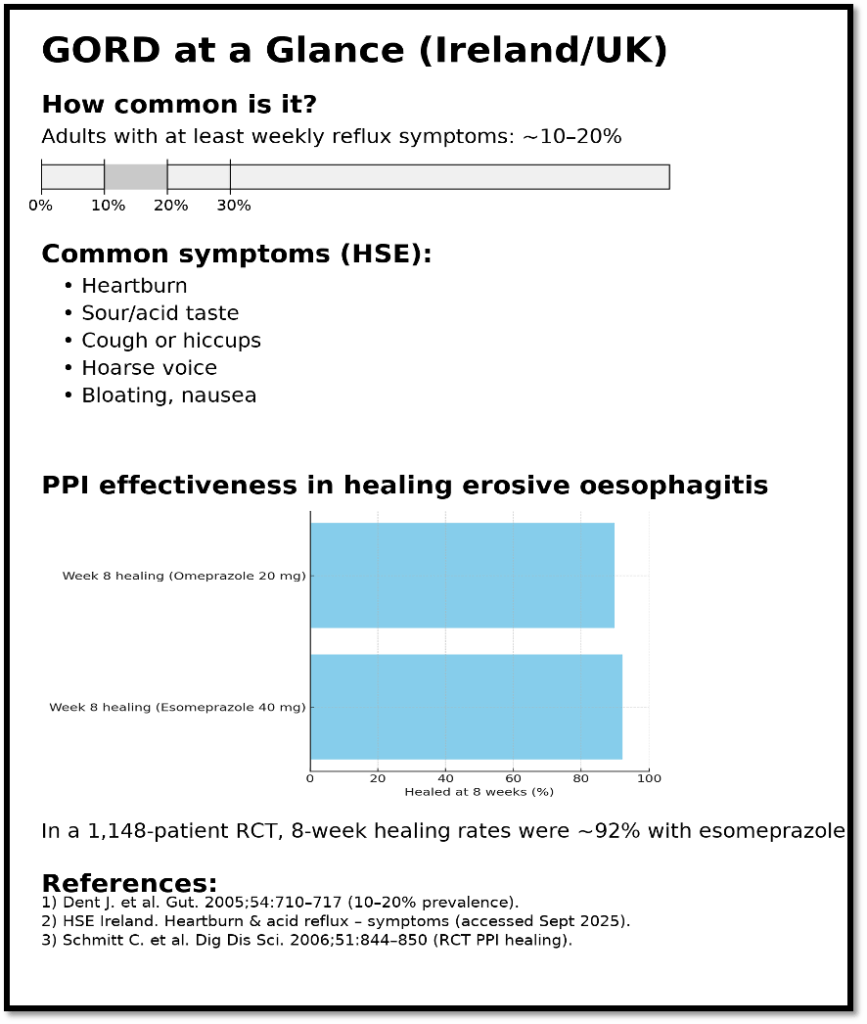

Within Ireland, the true prevalence of GORD is difficult to capture due to under-reporting and self-medication, but international studies suggest that up to 20% of adults experience reflux symptoms at least weekly. Extrapolating this to the Irish population indicates that several hundred thousand individuals are affected, with a knock-on effect on HSE resources and patient quality of life. Recent estimates suggest that reflux-related presentations account for a substantial proportion of GP consultations in primary care.

Up to 40% of infants may experience some degree of gastro-oesophageal reflux, often presenting as effortless regurgitation. This usually resolves by 12 to18 months as the lower oesophageal sphincter matures. However, a subset develops GORD with complications such as failure to thrive, feeding difficulties, or respiratory manifestations.

Part 1: Adults

Risk factors

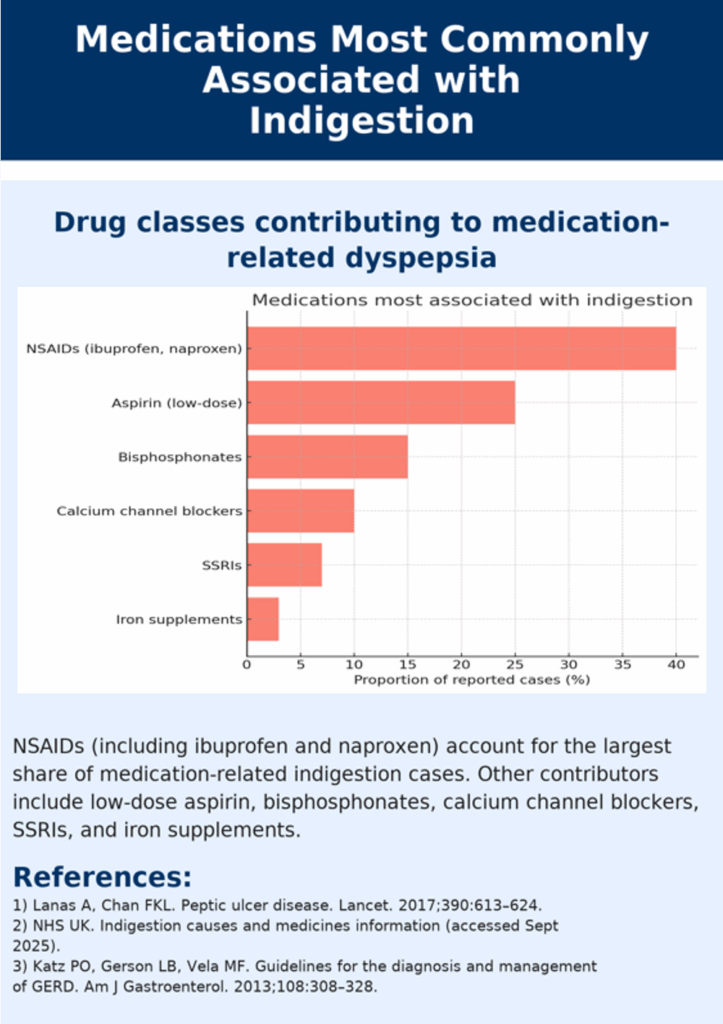

In adults, GORD is most common in those aged 40 and over, with prevalence increasing with age. Risk factors include obesity, smoking, high alcohol intake, pregnancy, and certain medications (e.g., calcium channel blockers, theophylline, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). Complicated disease, including erosive oesophagitis and Barrett’s oesophagus, is more likely in older men with longstanding symptoms. Alarm features for these include dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), unexplained weight loss, haematemesis (vomiting blood), or anaemia that may point towards oesophageal carcinoma and necessitate urgent referral.

This is in contrast to reflux in infants which is extremely common and, in most cases, benign and self-limiting.

Causes: From a pathophysiology perspective

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) arises when there is dysfunction in the protective mechanisms that normally prevent reflux of gastric contents into the oesophagus. While transient reflux episodes are common in healthy individuals, GORD develops when these episodes become excessive, prolonged, or associated with mucosal injury.

The most common cause of reflux is due to normal muscle relaxations happening more often if the stomach is bloated, or after fatty meals or alcohol, which can make acid reflux worse.

At the heart of GORD is a muscle called the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS), which acts like a valve between the stomach and food pipe. Normally, this valve stays tight (with a pressure of about 10–30 mmHg) to stop food and acid moving back up. Sometimes, it relaxes briefly on its own (called transient LOS relaxations or TLOSRs), which is normal, but these can happen more often if the stomach is stretched, after fatty meals, or with alcohol. In GORD, the valve may be weaker than normal, or these relaxations occur too often, letting stomach contents (acid or not) flow into the oesophagus.

The make-up of what comes back up also affects how severe symptoms are. Acid, digestive enzymes (like pepsin), and sometimes bile salts can all damage the food pipe lining. Pepsin stays active in acid and can directly injure the lining, while bile salts from the intestine can make the damage worse. This helps explain why some people keep having symptoms even when acid is reduced with medicines like PPIs.

Causes: on a more specific basis

Certain conditions and medication: Patients with diabetes mellitus are at particular risk due to autonomic neuropathy (including nerves oesophageal sphincter) meaning nerves don’t work as well and control muscle as well. Medications such as opioids and anticholinergics drugs can also exacerbate delayed emptying. Anticholinergic drugs are used to block certain body signals to reduce cramps, secretions, or bladder urgency (e.g., hyoscine, ipratropium, oxybutynin).

Polypharmacy: Another important insight relates to polypharmacy and long-term medication use. Drugs such as calcium channel blockers, nitrates, benzodiazepines, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have all been implicated in LOS relaxation and reflux exacerbation. Deprescribing initiatives have emphasised reviewing such agents in patients with poorly controlled GORD

Obesity: One of the strongest risk factors for GORD. Increased intra-abdominal pressure associated with central adiposity (accumulation of fat in and around the abdominal area) reduces LOS competence and promotes reflux. Adipose tissue also contributes through inflammatory mediators that may impair oesophageal mucosal defenses. This link between obesity and GORD has important public health implications in Ireland, where obesity prevalence continues to rise.

Type of diet: Even without obesity, diet can trigger reflux by relaxing the lower oesophageal sphincter or increasing stomach acid. Common culprits include fatty or fried foods, spicy meals, citrus, tomatoes, chocolate, caffeine, alcohol, and carbonated drinks. Large meals or late-night eating also raise stomach pressure, promoting

Pregnancy: Another common reflux cause, with prevalence rates up to 80% in the third trimester. Hormonal influences, particularly progesterone-induced smooth muscle relaxation, combine with mechanical pressure from the enlarging uterus to lower LOS tone. While symptoms usually resolve postpartum, treatment options for pregnant women should focusing on lifestyle modification and alginate-based therapy before considering pharmacological interventions.

Smoking: Weakens lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) tone and reduces salivary bicarbonate, worsening reflux.

Alcohol: particularly beer, wine, and spirits, increases gastric acid production and promotes LOS relaxation.

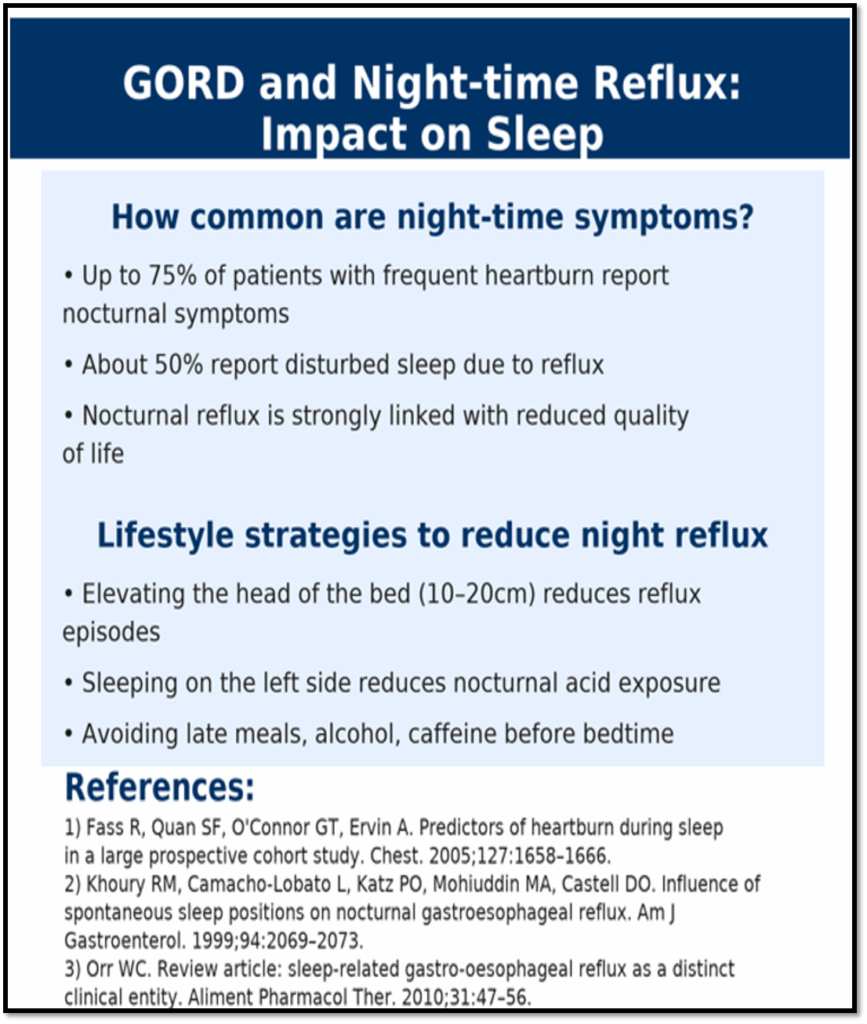

Night-time reflux: Is more common because lying down removes gravity’s help, slowing stomach emptying and letting acid flow back more easily. Lower saliva production at night also reduces natural acid neutralisation, increasing irritation of the oesophagus.

Microbiome: There is also growing recognition of the role of the microbiome (beneficial bacteria in the gut) and low-grade inflammation in oesophageal health. Early evidence suggests alterations in the oesophageal and gastric microbiota may influence mucosal resilience and prevalence of reflux, though clinical application remains in its infancy. Furthermore, studies have highlighted that bile reflux may be more clinically relevant than previously thought

Clinical presentation and symptoms

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) can present in a wide variety of ways, from the classic symptom profile of heartburn and regurgitation to atypical manifestations that overlap with respiratory, ENT, and even dental conditions.

The hallmark symptom of GORD is heartburn, described as a burning sensation rising from the epigastrium (top of stomach), into the chest, often worse after meals or lying down. Regurgitation of sour or bitter-tasting gastric fluid into the throat or mouth is another classic feature. These symptoms are frequently aggravated by large meals, fatty or spicy foods, alcohol, and supine posture (lying on the back). Relief with antacids or alginate therapy is highly suggestive of acid reflux as the underlying cause.

For many patients, symptoms are intermittent, but in others they may be persistent, leading to significant impairment in quality of life, sleep disruption, and work absenteeism.

Beyond the classic profile, GORD is increasingly recognised as a cause of extra-oesophageal symptoms. Chronic cough, hoarseness, sore throat, globus sensation (feeling of having a lump, tightness, or foreign body stuck in the throat), asthma exacerbations, and non-cardiac chest pain are among the atypical presentations. Dental erosions and halitosis (bad breath) may also arise from recurrent acid exposure. Such cases can be diagnostically challenging, as reflux is often one of several contributing factors.

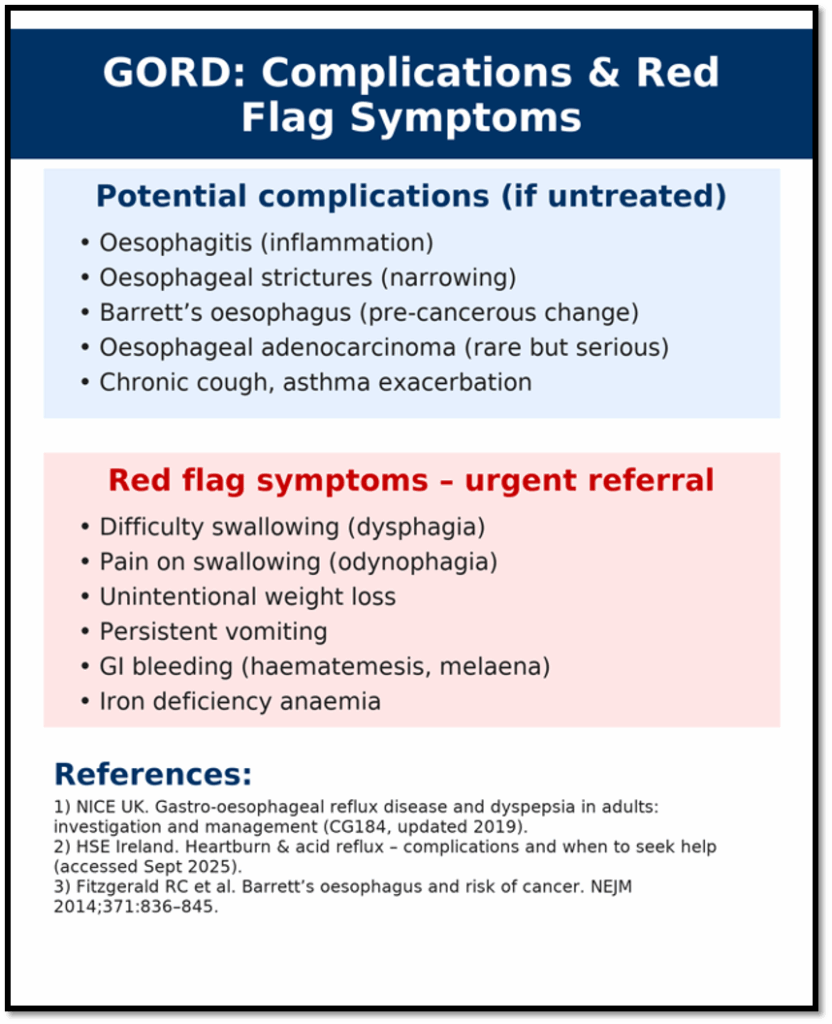

While most cases of GORD can be safely managed in primary care, there must be vigilance for red flag features that may suggest oesophageal cancer, peptic ulcer disease, or other serious pathology. These include:

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing).

- Odynophagia (pain on swallowing).

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Gastrointestinal bleeding (haematemesis) or melaena (black, sticky, tar-like stools which can indicate bleeding further up the GI tract)

- Iron-deficiency anaemia.

- Persistent vomiting.

- New-onset symptoms in patients over 55 years.

Any of these features should prompt urgent referral to a GP for further investigation, typically by endoscopy.

Complications of GORD

Most patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) experience symptoms that are troublesome but not life-threatening, a subset progress to complications that carry significant morbidity and mortality.

Barrett’s oesophagus represents a metaplastic change in the distal oesophageal epithelium (the cells lining the oesophagus have changed into a different type of cell), where normal squamous cells are replaced by columnar epithelium (i.e.) the normal flat cells in the food pipe have changed into tall, gland-like cells. This occurs in response to chronic acid and bile exposure and is considered a premalignant condition. The estimated prevalence among patients with long-standing reflux symptoms is between 5–15%. In Ireland, awareness of Barrett’s has increased in recent years, with surveillance endoscopy programmes in place for high-risk patients.

Chronic reflux can lead to scarring and narrowing of the oesophagus, resulting in peptic strictures i.e., narrowing of the oesophagus. These present with progressive dysphagia, initially to solids and later to liquids, and can significantly impair nutrition and quality of life. Endoscopic dilation is procedure to open up narrowing in the oesophagus, ensuring easier swallow is often required.

Although less common, persistent exposure to acid and pepsin can result in deep mucosal ulceration. These ulcers are painful, may bleed, and increase the risk of stricture formation. Clinically, patients may present with chest pain, odynophagia (painful swallowing), or anaemia. As with peptic ulcer disease, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use exacerbates risk.

The most concerning complication of GORD is oesophageal adenocarcinoma (as form of cancer), which develops in a proportion of patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Ireland has one of the highest rates of oesophageal cancer in Europe, with around 450 to 500 new cases diagnosed annually. The majority are adenocarcinomas arising in the context of chronic reflux. Prognosis remains poor, with five-year survival below 25%, largely due to late presentation. This underscores the importance of vigilance; alarm features such as dysphagia, weight loss, or persistent vomiting arise.

Diagnosis and investigations

The diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is primarily clinical, based on the patient’s symptom history and response to empirical treatment.

In most adults, GORD is diagnosed clinically. Typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation, particularly if relieved by antacids or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), are sufficient to establish a working diagnosis without invasive testing. This pragmatic approach is endorsed by international and Irish practice, helping to reduce unnecessary investigations, cost, and patient inconvenience. Empirical trials of acid suppression for 4–8 weeks are often used as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool. However, atypical symptoms or poor response to initial treatment should prompt further evaluation.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (oesophagogastroduodenoscopy, OGD) remains the gold standard investigation for suspected complications of reflux, such as oesophagitis, strictures, Barrett’s oesophagus, or malignancy. OGD is where a doctor uses a thin flexible camera tube (endoscope) to look inside the oesophagus. Endoscopy is not routinely indicated in all patients with reflux but is recommended when alarm features are present (dysphagia, weight loss, anaemia, bleeding, persistent vomiting, or age over 55 with new-onset symptoms).

In Ireland, access to endoscopy has been constrained by waiting lists, a situation worsened during and since the COVID-19 pandemic. Referral is prioritised when red flags are identified, so surveillance is necessary in those diagnosed with Barrett’s oesophagus.

In cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or symptoms persist despite therapy, ambulatory pH monitoring is used. A catheter or wireless capsule measures oesophageal acid exposure over 24–48 hours. Combined pH-impedance testing can also detect non-acid reflux, particularly relevant in patients with ongoing symptoms on PPIs. These investigations are mainly available through specialist gastroenterology services.

Although not diagnostic of GORD itself, oesophageal manometry assesses oesophageal motility and LOS

pressure. It is particularly useful when surgical or endoscopic anti-reflux procedures are being considered.

In infants, reflux is common and usually physiological, meaning it something that happens naturally in the body rather than external factors. Diagnosis of GORD in this group relies on careful clinical assessment rather than routine investigations. Red flag features in infants include poor weight gain, haematemesis, feeding refusal, or respiratory complications. Investigations such as pH monitoring or endoscopy are rarely needed unless complications or atypical presentations are suspected.

Cost burden

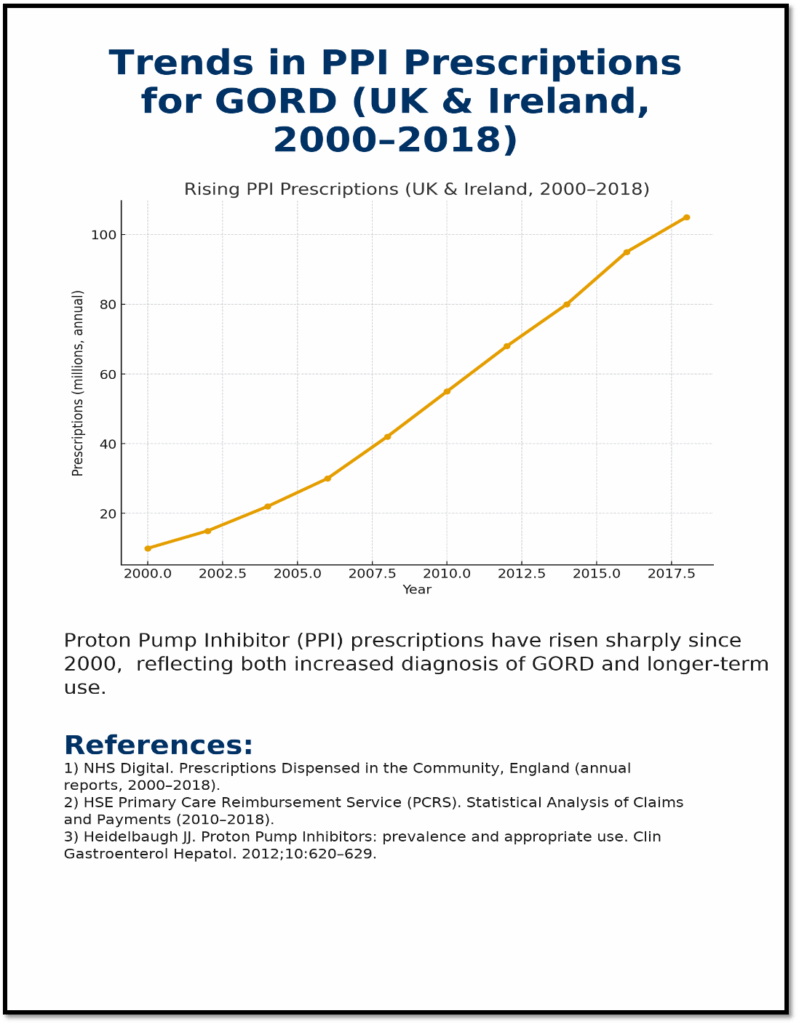

The cost burden on the health service remains considerable. PPIs, in particular, represent one of the highest expenditure categories within the community drugs schemes. While generic substitution and prescribing guidelines have moderated costs in recent years, expenditure remains in the tens of millions of euros annually. Ensuring PPIs are used appropriately, deprescribing where indicated, and reinforcing lifestyle advice are therefore more important than ever. Beyond health service financial considerations, poorly controlled GORD contributes to reduced work productivity, sleep disturbance, and impaired quality of life, further underscoring the importance of effective management as it effects overall productivity in the economy.

Pharmacological management in adults

Pharmacological management forms the cornerstone of treatment for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), both for symptom relief and for prevention of complications.

Antacids

Antacids provide rapid, short-term relief of heartburn by neutralising gastric acid. Common preparations available in Ireland include calcium carbonate, magnesium hydroxide, and aluminium hydroxide, either singly or in combination. While effective for mild, infrequent symptoms, their short duration of action limits use as long-term therapy.

Side effects can include diarrhoea with magnesium salts or constipation with aluminium salts. Drug interactions are clinically relevant. Examples include the facts antacids can impair absorption of medicines such as tetracyclines, bisphosphonates, levothyroxine, and some fluoroquinolones. Antacids can also increase the effect of Sodium Valproate (Epilim®). Antacids can also damage enteric coating which many medicines have to protect the stomach from irritation. Best practice is to separate administration by at least two hours.

In practice, antacids are most useful for occasional breakthrough symptoms, often in combination with alginates. They are widely available OTC, and pharmacists should ensure patients understand they are for symptomatic relief only, not long-term control of GORD.

Alginates

Alginates (e.g., Gaviscon®) act by forming a viscous “raft” that floats on the gastric contents, reducing reflux episodes, especially postprandially and when supine. They are particularly effective for regurgitation-dominant symptoms and are safe in pregnancy, making them a valuable first-line option in this group. Taking after meals and before bedtime maximise benefit. Side effects are minimal, though sodium load should be considered in patients with hypertension or heart failure. Alginates are available OTC, and pharmacists often recommend them as initial therapy for infrequent or pregnancy-related reflux.

H2RAs

H2Ras (H2 receptor antagonists) reduce gastric acid secretion by blocking histamine H2 receptors on parietal cells. Products available in Ireland reduced when ranitidine was withdrawn a few years ago due to NDMA contamination concerns. NDMA contamination refers to the presence of N-nitroso-dimethylamine (NDMA), a probable human carcinogen, in medicines.

Famotidine is the most widely available option, OTC (Pepcid®) and on prescription. Famotidine is unlicensed in Ireland on prescription Typical dosing is 20 mg once or twice daily, with up to 40 mg twice daily. H2RAs are generally well tolerated, with occasional headache, dizziness, or diarrhoea. Interactions are less significant than with PPIs, but cimetidine (rarely used) is a potent CYP450 inhibitor and can interact with warfarin, theophylline, and phenytoin. Tolerance may develop with long-term use, leading to reduced effectiveness.

H2RAs are positioned as a step-up from alginates/antacids in mild to moderate GORD, especially for patients with nocturnal symptoms. They may also be useful as adjunctive therapy in patients on PPIs who experience breakthrough symptoms.

PPIs

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) remain the mainstay of treatment for frequent or severe GORD. In Ireland, PPIs include omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole, and esomeprazole. OTC formulations are limited to low-dose omeprazole and pantoprazole for short courses, while higher doses and other PPIs are prescription-only.

Dosing:

- Omeprazole: 20 mg once daily, up to 40 mg for refractory cases

- Lansoprazole: 15–30 mg once daily.

- Pantoprazole: 20–40 mg once daily.

- Esomeprazole: 20–40 mg once daily.

- Rabeprazole: 20 mg once daily.

PPIs are best taken 30–60 minutes before the first meal of the day for maximal acid suppression. Some patients may require twice-daily dosing if symptoms are uncontrolled. Step-down therapy should be considered once control is achieved.

Interactions: Omeprazole and esomeprazole inhibit CYP2C19 and may reduce activation of clopidogrel, potentially reducing antiplatelet efficacy. This is clinically important for cardiovascular patients and alternatives such as pantoprazole may be advised. PPIs may also interact with warfarin, phenytoin, and methotrexate.

Long-term safety: Long-term PPI therapy has been associated with risks including hypomagnesaemia, vitamin B12 deficiency, osteoporosis-related fractures, and enteric infections such as clostridioides difficile. While absolute risks are small, they are clinically important in older adults and those on polypharmacy. Recent HSE deprescribing initiatives encourage GPs and pharmacists to review chronic PPI use and step down or discontinue where appropriate. Prescription-only PPIs and higher doses are appropriate for confirmed GORD, erosive oesophagitis, or patients with complications such as Barrett’s oesophagus.

Non-Pharmacological and Lifestyle Management

Lifestyle modification is a cornerstone of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) management, complementing pharmacological therapy and, in some cases, reducing the need for long-term medication.

Dietary triggers play a significant role in reflux symptoms. High-fat meals, spicy foods, chocolate, citrus fruit, caffeine, and carbonated drinks are well-established contributors. In the Irish context, traditional diets often include fried foods, processed meats, and high-fat dairy, all of which can exacerbate reflux.

Portion size and meal timing are equally important; late-night eating, common with shift work or social occasions, worsens nocturnal symptoms. Advise patients to eat smaller, more frequent meals and to avoid lying down for at least two to three hours after eating.

Obesity is one of the strongest risk factors for GORD, with excess intra-abdominal pressure promoting reflux. With over 60% of Irish adults classified as overweight or obese, weight reduction is a critical strategy. Even modest weight loss of 5–10% can significantly reduce reflux symptoms. Pharmacists can play a proactive role by signposting to HSE weight-management programmes and offering practical advice around portion control, exercise, and healthy substitutions.

Smoking weakens lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) tone and reduces salivary bicarbonate, worsening reflux. Ireland’s falling smoking rates are encouraging, but prevalence remains notable in socioeconomically deprived groups.

Alcohol, particularly beer, wine, and spirits, increases gastric acid production and promotes LOS relaxation. While total abstinence may not be realistic, advising moderation and avoidance of alcohol close to bedtime can yield benefits.

Night-time reflux is common and disruptive. Patients should be advised to elevate the head of the bed by 10–20 cm using blocks or wedges, rather than additional pillows, which can worsen flexion. Avoiding late meals and alcohol before bed also improves nocturnal control. Left-side sleeping has been shown to reduce reflux episodes compared to lying on the right side.

Summary of self-care techniques to relieve symptoms of GORD.

- Targeting weight loss for those obese or overweight will help reduce the pressure on the stomach. This in turn will reduce the severity and frequency of symptoms.

- Avoid tight-fitting clothing. Loose fitting clothing, especially trousers will reduce pressure on the abdomen and the lower oesophageal sphincter.

- Stop smoking.

- Reduce or avoid consumption of heartburn inducing foods (i.e.) fatty, fried or spicy. Reducing consumption of alcohol, chocolate and caffeine will also alleviate heartburn.

- Adjust eating habits. Little and often is easier for the digestive system to manage and process than the traditional three meals a day model.

- Avoid eating late in the evening to ensure that the stomach is empty at bedtime.

- Drink alcohol only in moderation with meals.

- Take time to enjoy food; take the time to chew and digest what we eat. This puts less strain, so the stomach has to “work” less. The reverse is also true; eating quickly means the stomach does more work and exacerbates symptoms of GORD.

- Avoid bending too much, especially after meals.

- Raise the head of the bed by 10 to 20cm by placing a piece of wood under it. This can help prevent stomach contents from rising into the oesophagus.

Part 2: Infants and children

Management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) in infants and children differs significantly from adults, requiring careful consideration of developmental physiology, safety of medicines, and the importance of conservative measures.

In infants, reflux is frequently physiological, which means it’s due to something that happens naturally in the body rather than external factors. It peaks at around 4 months of age and resolving by 12 to18 months. Most cases require no medical intervention, and reassurance is the most valuable approach. Conservative strategies include smaller, more frequent feeds, avoidance of overfeeding, ensuring infants are burped regularly, and maintaining an upright posture after feeding. Parents should be counselled that symptoms such as occasional regurgitation are normal provided weight gain and development are unaffected.

Pharmacological management in infants and children

Changing feed

Feed thickeners are often used as a first-line measure when conservative management alone is insufficient. In Ireland, commercial products such as Carobel® (carob bean gum-based) are commonly used to increase the viscosity of feeds, reducing regurgitation. Pharmacists should provide clear instructions on preparation, highlighting the importance of avoiding excessive thickening that may impair feeding.

There are also ready-thickened feeds such as Enfamil AR® or SMA Staydown®. Enfamil AR® powder is used as an infant milk from 0 to 12 months, follow the instructions on the side of the container. As this product is a pre-thickened infant milk, it may need to be switched to a faster flow teat to help the infant or child suck it. The example given here are only some of many feed available as thickened feeds and used as examples only and are I am in no way endorsing them as superior than other brands.

If breastfeeding and the infant is having problems with bringing up food, Gaviscon® Infant sachets may be used instead of the above mentioned products.

Alginates

Alginates (e.g., Gaviscon® Infant) are another option in formula-fed infants. They act by forming a raft barrier to limit reflux, though their sodium content means they should not be used long-term or in infants under 4.5 kg. Parents should be advised to use only under medical advice and to avoid combining alginates with feed thickeners, as this may cause bowel obstruction.

Dosage depends on the weight of the infant. Gaviscon® Infant sachet(s) can be mixed with cool boiled water, milk feed or expressed breast milk. Gaviscon® Infant sachet(s) should not be administered more than six times in 24 hours. Gaviscon® Infant should not be given to premature infants, young children who are ill with a high temperature, diarrhoea, vomiting, or if already using a food thickener.

PPIs

Pharmacological acid suppression is reserved for infants and children with confirmed GORD associated with oesophagitis, faltering growth, or significant complications. PPIs such as omeprazole and lansoprazole are the mainstay, though they are not licensed for use in very young infants and are generally initiated by a paediatrician. Omeprazole is available as dispersible tablets (Losec MUPS®) which can dispersed in water, facilitating administration. A licensed version of omeprazole (Pedippi Oral Suspension) is available on prescription.

Dosage of omeprazole: Newborn infant under 4 weeks, 700mcg/kg once daily, increased, if necessary, after 7 to 14 days to 1.4mg/kg once daily. Child 1 month to 2 years, 700mcg/kg once daily, increased if necessary to 3mg/kg max. 20mg once daily.

Dosage range for omeprazole by weight:

- Childs body weight 10-20 kg: 10 mg once daily (max 20 mg/day)

- Childs body weight over 20 kg: 20 mg once daily (max 40 mg/day)

Long-term safety is an important consideration. As in adults, PPIs have been associated with risks including respiratory and gastrointestinal infections, micronutrient malabsorption, and potential effects on the gut microbiome. These risks underscore the importance of ensuring treatment is indicated, regularly reviewed, and discontinued as soon as possible.

H2RAs

H2RAs such as famotidine reduce the amount of acid in the stomach is sometimes used, though not very frequently. It is only available in unlicensed (ULM) version, and the liquid ULM version is very expensive. Their effectiveness may be reduced with long-term use due to tolerance, and they are less potent that PPIs. Ranitidine (Zantac®), a type of H2 antagonist that came in liquid form was often used for GORD in infants until it was recalled in 2019.

Domperidone

Domperidone helps tighten oesophageal sphincter. This will help stop food from flowing back into the oesophagus. It comes in liquid or rectal (suppository) form for infants and children but is only available with a prescription. Directions: By mouth; over one month and body weight up to 35kg, 250 – 500mcg/kg three to four times a day, body weight 35kg and over 10 – 20mg three to four times daily, max. 80mg daily. By rectum; body weight over 15kg one 30mg Motilium® Suppository twice a day, body weight over 35kg 60mg twice daily. Some young children taking domperidone may get mild diarrhoea.

Pharmacist input

When a child is prescribed likes of a PPI, pharmacists should provide practical guidance on preparation and administration, including how to disperse tablets or measure liquid formulations accurately. Emphasis should be placed on adherence, timing of doses relative to feeds, and the importance of follow-up with a paediatrician.

In paediatric GORD, medicines play only a small role, with conservative and dietary strategies being most effective for the majority.

Part 3: Surgical and endoscopic interventions

More frequently adults rather than children

While the majority of patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) achieve adequate control with lifestyle modification and pharmacological therapy, a minority require surgical or endoscopic intervention.

Surgical or endoscopic approaches are generally reserved for patients with severe reflux symptoms or complications that are not adequately controlled with optimal medical therapy. Indications include:

- Persistent, severe symptoms despite high-dose PPIs.

- Objective evidence of reflux with oesophagitis, Barrett’s oesophagus, or strictures.

- Patients who are intolerant of PPIs or unwilling to remain on long-term medication.

- Selected younger patients with documented reflux who prefer a definitive solution.

Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication remains the gold standard surgical treatment, reinforcing the lower oesophageal sphincter by wrapping the gastric fundus around the distal oesophagus. Partial wraps (Toupet or Dor procedures) may be used in patients with impaired oesophageal motility. Surgical outcomes are generally good, though side effects such as dysphagia, bloating, and gas trapping may occur.

Newer, less invasive options include endoscopic fundoplication, radiofrequency therapy (Stretta), and magnetic sphincter augmentation (LINX device). While some are available internationally, access in Ireland remains limited, with most patients referred abroad for novel therapies. Currently, surgery remains the main definitive option within the HSE system.

Part 4: Role of the Pharmacist in GORD Management

For adults and children

In Ireland, pharmacists are often the first point of contact for patients with GORD. Their role combines OTC treatment advice, patient counselling, and referral, ensuring safe, effective, and cost-efficient care.

OTC treatment is the starting point for many. Pharmacists assess suitability and recommend antacids or alginates for quick relief of mild, infrequent symptoms, or short 14-day courses of low-dose PPIs (e.g., omeprazole, pantoprazole) for frequent heartburn. They emphasise correct use, short-term duration, and refer if symptoms persist or repeated requests occur.

Counselling is central. Pharmacists educate on proper PPI timing (30–60 minutes before food), treatment duration, lifestyle measures, and risks of long-term use (e.g., hypomagnesaemia, fractures, infections). In children, they provide reassurance about normal reflux, safe advice on feed thickeners/alginate use, and reinforce the need for medical oversight.

Referral is vital when red flags appear including dysphagia, weight loss, persistent vomiting, bleeding, or new reflux in patients over 55. Pharmacists also escalate care when OTC therapy fails, when recurrent OTC PPI use is sought, or when children present with warning signs. They may liaise with prescribers on drug-induced reflux (e.g., calcium channel blockers, NSAIDs).

Early identification: By combining early identification, safe self-care support, education, and timely escalation, pharmacists reduce inappropriate medicine use, safeguard against complications, and support HSE resource management. As highly accessible healthcare professionals, they are at the frontline of GORD management in Ireland, ensuring patient-centred care from first presentation through long-term support.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults: investigation and management (NG1). 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in children and young people: diagnosis and management (NG1 update). 2015, updated 2023.

- Health Service Executive (HSE). Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPI) Prescribing and Deprescribing Guidance. 2023.

- Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA). Summary of Product Characteristics – Proton Pump Inhibitors (various).

- Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(8):1900–1920.

- El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014;63(6):871–880.

- Gyawali CP, Kahrilas PJ, Savarino E, et al. Modern diagnosis of GERD: the Lyon Consensus. Gut. 2018;67(7):1351–1362.

- Scarpignato C, Gatta L, Zullo A, Blandizzi C. Effective and safe proton pump inhibitor therapy in acid-related diseases – A position paper. BMC Med. 2016; 14:179.

- Spechler SJ, Souza RF. Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):836–845.

- Fass R, Shapiro M, Dekel R, Sewell J. Systematic review: proton-pump inhibitor failure in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease – where next? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(2):79–94.

- Savarino V, Di Mario F, Scarpignato C. Proton pump inhibitors in GORD: an overview of their pharmacology, efficacy, safety, and future perspectives. Drugs. 2018;78(11):1143–1166.

- Katz PO, Dunbar KB, Schnoll-Sussman FH, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(1):27–56.

- Smyth CM, O’Morain CA. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: diagnosis and management. BMJ. 2018;363: k4090.

- Hampel H, Abraham NS, El-Serag HB. Meta-analysis: obesity and the risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(3):199–211.

- Hvid-Jensen F, Pedersen L, Drewes AM, Sørensen HT, Funch-Jensen P. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(15):1375–1383.

- Herregods TVK, Bredenoord AJ, Smout AJP. Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: new understanding in a new era. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(9):1202–1213.

- Moayyedi P, Eikelboom JW, Bosch J, et al. Safety of proton pump inhibitors based on a large, multi-year, randomized trial of patients receiving rivaroxaban or aspirin. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(3):682–691.

- Vaezi MF, Yang YX, Howden CW. Complications of proton pump inhibitor therapy. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):35–48.

- Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66(3):516–554.

- Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Wu Y, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53(4):470–481.

- Vakil N, Vaezi MF. Functional heartburn: approaches to management. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(3):732–744.

- Frazzoni M, Savarino E, de Bortoli N, et al. Analyses of impedance-pH parameters in GERD patients: evidence that refractory reflux symptoms are mostly not due to reflux. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29(5): e12910.

- Bochenek WJ, Fennerty MB. Medical therapy for reflux disease: the role of the primary care physician. J Fam Pract. 2003;52(6):479–486.

- National Cancer Registry Ireland. Oesophageal cancer in Ireland annual report. 2023. World Gastroenterology Organisation (WGO). Global guideline: GERD. 2017 update